History of Daylight Saving Time

The underlying reason for Daylight Saving Time—or “summer time” as it’s called in other places around the world—is to make better use of the daylight. Thus, clocks are changed in the spring to, essentially, shift an hour of daylight from the morning to the evening. Then, in the fall, we return to Standard Time and shift an hour of daylight back from the evening to the morning.

But first, let’s get one thing straight. It’s Daylight “Saving” Time, not Daylight “Savings” Time. No “S”. Adjective versus verb. Got it? Great : )

Before we embark on the interesting and oftentimes colorful evolution of Daylight Saving Time, we must first understand how modern Standard Time came to be.

In the beginning, there was Solar Time

Since the dawn of man, time has been measured based on the sun’s position in the sky. Sundials were the first invention to keep track of time. Because they had no moving parts, sundials were easy to build and proliferated quickly. The time on a sundial is logically called solar time, or true local time, whereas the time on a clock is called mean solar time.

The ancient Romans and Greeks advanced the concept of tracking time by inventing water clocks. which used the flow of water in or out of a vessel to measure the passage of time. Instead of using the same vessels each month, the Romans used different sizes for different months, meaning their “hours” would be longer or shorter based on the month. Their goal was to have a set number of “hours” in a day between sunrise and sunset, so they had to change the length of each vessel depending on how much time there was between the sun rising and setting.

Thus, sundials and water clocks were the clocks of yore until mechanical clocks appeared well into the Middle Ages. Time began to be based on a consistent division of the day regardless of day or night like we have today, where a day is divided by hours, minutes and seconds.

Despite this wonderful new invention, cities would set their own time by measuring the sun’s position, and, therefore, everyone would be on slightly different time.

Standard Time is born in Britian

With different cities and regions having their own local time, as technological progress advanced our ability to communicate and travel between localities, you can imagine the confusion that could have ensued.

Britain became was the first country to establish one Standard Time throughout the country in response to the railways’ overt criticisms of local mean time. Thus, in November 1840—the Great Western Railway was the first to follow “London” time. Soon, other railways followed, and by 1847, most railways used this time.

It was consequently called “Standard Time” because it standardized the time across Britain. That name stuck and we still use that nomenclature today.

London time—also became known as Greenwich mean time (GMT)—is the time at the Royal Observatory’s Shepherd Gate Clock in—you guessed it—Greenwich, England. GMT remains the same all year round, and is the time against which the rest of the world’s time is measured.

Eventually, by 1855, the majority of British public clocks were set to GMT, and on 2 August 1880, the Statutes (Definition of Time) Act took effect—essentially changing the legal system to GMT.

Standard Time comes to the U.S.A.

Now, let’s hop across the pond and examine the U.S.’s convoluted Standard Time timeline.

William Lambert—an amateur astronomer—was the first person in the U.S. to preach the necessity for time standardization. The recurring problem was that time was a local construct with most towns and cities using some type of local solar time, typically based on “high noon”—the time when the sun was the highest in the sky. However, the lack of consistency caused problems as more modern technology such as the advent of the railroad made each city interconnected.

In 1809, Lambert unsuccessfully recommended the concept of time meridians—or different time zones—to Congress. In 1870, Charles Dowd offered a similar suggestion that was also rejected; however, Dowd’s second proposal in 1872 was ultimately adopted on 18 November 1883 by U.S. and Canadian railways, and, subsequently, four continental time zones emerged to put an end to this craziness.

The railroads played a crucial part in this evolution. The myriad of different local times resulted in a scheduling nightmare where dozens of different arrival and departure times were listed for each train. There were some train table examples that showed over 100 local times which varied by more than 3 hours. Railroad executives asserted that timekeeping required greater uniformity to ensure efficiency, and—in a truly smart move—the companies created four different continental time zones that are quite similar to the ones still in use today.

Ultimately, the Standard Time Act was enacted on 19 March 1918 with responsibility given to the Interstate Commerce Commission which, later, passed the buck to the newly-created Department of Transportation in 1966.

Standard Time spreads across the World

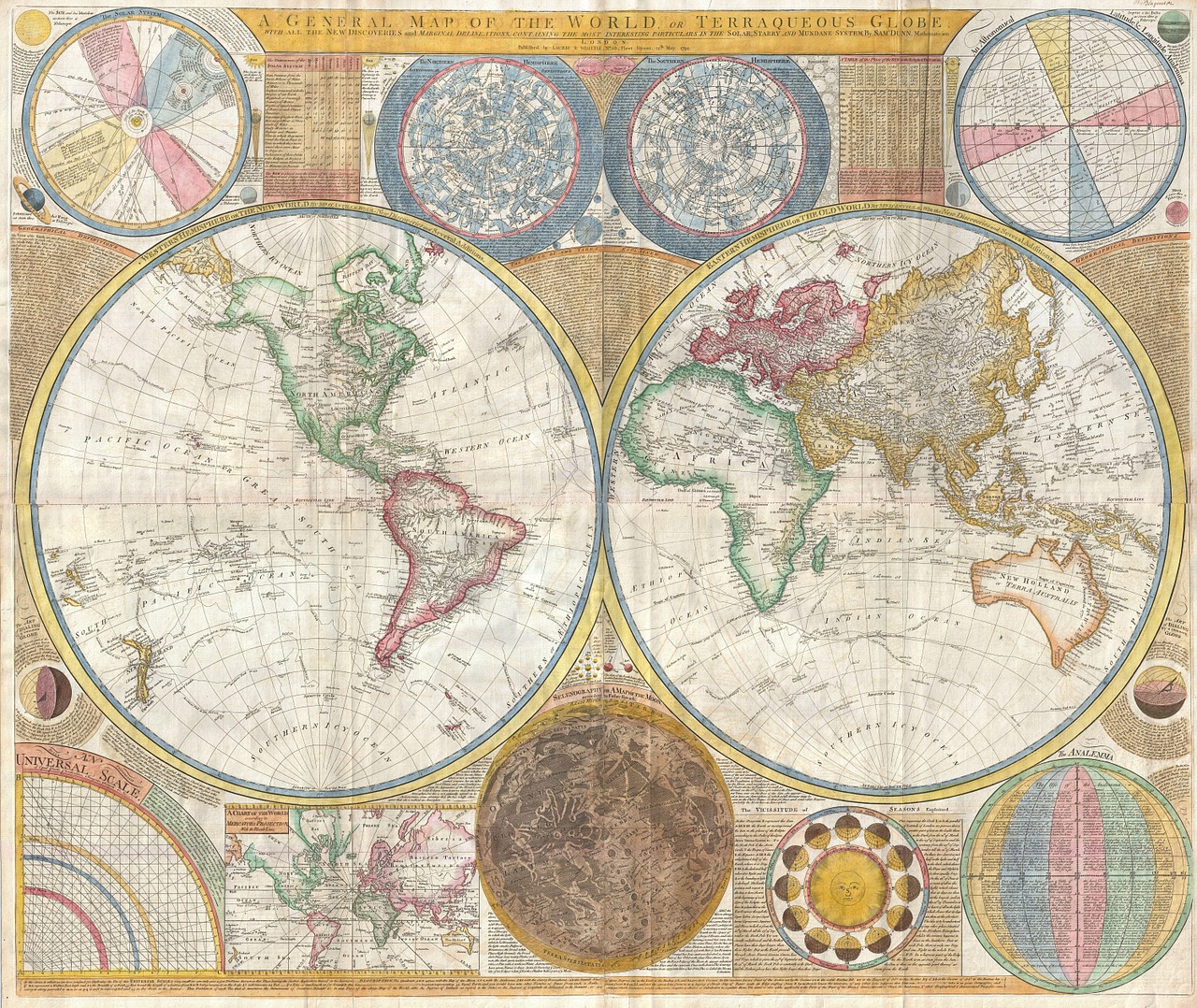

Building on the railways’ acceptance of a Standard Time with different zones, Canadian civil and railway engineer Sandford Fleming proposed a concrete concept of worldwide time zones.

Just as local travel and communications required local cities times to be in sync, world travel and communications began to have the same requirements.

The first Geographical Congress convened in 1871 and passed a motion to generally utilize Britain’s GMT time for passage charts and suggested an overall standardization within 15 years.

Fleming was ultimately responsible for convening the International Prime Meridian Conference in 1884 in which the current system of international Standard Time was adopted.

Finally, the whole world became in sync and issues with communication and travel were greatly lessened. Okay, Phew! Well, then the concept of Daylight Saving Time began. That story is still unfolding.

The Myth surrounding Ben Franklin

The earliest concept of Daylight Saving Time is commonly associated with Benjamin Franklin who—while in Paris in 1784 as an American delegate—penned an essay on the thrift of artificial versus natural lighting entitled An Economic Project. Relatedly, however, Franklin submitted several bagatelles—French for a relatively insignificant trifle—to the Journal de Paris which included several tongue-in-cheek suggestions as to how Parisians could save money.

Specifically, Franklin noted that Parisians rarely awakened before noon, and they were fairly ignorant that the sun rose earlier each day approaching the summer solstice for longer days and that, subsequently, the days grew shorter each day approaching the winter solstice. He postulated that if Parisians rose in the morning and used sunshine instead of candles, they would save significant francs on evening candles: $200 million, in fact. Essentially, he asserted—correctly, as a matter of fact—that they were wasting half of the day sleeping. While his proposed new regulations—steeped in humor and sarcasm that included taxing window shutters, stopping non-emergency coach traffic at night, and firing cannons in the morning to get “sluggards” with the program—would likely not reach fruition, his ideas did, in fact, spark discussion that ultimately led to the concept of Daylight Saving Time we know of today.

So, while Franklin merely pointed out how daylight could be best utilized by being “early to bed and early to rise,” he did not “invent” Daylight Saving Time for which he is constantly—yet erroneously—credited. The “healthy, wealthy, and wise” part is still all Poor Richard—and remains words of wisdom.

The Canadians were actually First

Although many may still give the prize to either Austria or Germany as the first countries to implement Daylights Saving Time, the prize for starting the Daylights Saving Time movement would actually go to the Canadians.

In 1908, at the start of July, the people of Port Arthur in Ontario pushed their clocks forward by an hour. It proved to be effective, and soon other cities and towns followed suit. In 1914, Regina in Saskatchewan started using Daylight Saving Time. With Winnipeg and Brandon in the following year of 1916 following suit.

Daylight Saving Time comes to the U.S.A.

While parts of Canada did start using Daylight Saving Time first, there was comprehensive consideration going on in Europe. In the early 1900s, London builder William Willett was the first to seriously advocate the concept of Daylight Saving Time. In his pamphlet, Waste of Daylight (1907), Willett proposed advancing the clocks by 20 minutes on each Sunday in April and then turning them back them the same amount during the four Sundays in September.

Soon after Willett’s emphatic lobbying for Daylight Saving Time, Robert Pearce introduced a bill in the House of Commons mandating adjusting the clocks; however, significant opposition, especially from farmers—and, of course, much ridicule—killed the bill multiple times. Willett died in 1915, and the following year—Germany became that was the first full country to adopt Daylight Saving Time on 1 May 1916—Britain eventually enacted Willett’s scheme—but not without tenuous contention. Opposition, prejudice, and confusion were the order of the day.

After World War I, Britain’s Parliament passed additional acts concerning “summer time,” most of which concerned starting days (the third Saturday in April) and ending days (the day following the first Saturday in October.) Then, during World War II, British clocks were advanced by two hours—resulting in “double summer time” with the clocks remaining on regular “summer time” during the winter.

Are you confused yet? No? Well, don’t worry, there’s even more fun ahead.

Daylight Saving Time spreads through the Western World

Britain was an early advocate of summer time during World War I. However, shortly before its acceptance and soon after Germany’s implementation, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Sweden, Turkey, Tasmania, Nova Scotia, and Manitoba adopted a form of Daylight Saving Time. Britain jumped on the bandwagon three weeks later, and, in 1916, Australia and Newfoundland joined the club.

The U.S. didn’t formally adopt the plan until 1918 with its “act to preserve daylight and provide Standard Time for the United States.” The law set Daylight Saving Time to commence on 31 March 1918.

Farmers and Agriculture Repeal DST

As would be expected, the U.S.’s entrance into the Daylight Saving Time playing field caused significant opposition and lobbying, particularly by the agriculture industry which was deeply opposed to the time change during the war. For farmers and other agrarians, it was the sun—not the hands of a clock—that dictated their schedules.

“After all, dew doesn’t evaporate at a specific time, cows typically aren’t too keen on an earlier milking, workers worked less since they came and went according to the clock, and those darn roosters sure can’t tell time.”

This massive lobbying led to the 1919 repeal of Daylight Saving Time despite the woes of retail and recreational businesses that championed the time change because later daylight spurred more economic activity for shops and activities. Consequently, the experiment of Daylight Saving Time was repealed within a year and relegated to a local option with a few states and cities continuing it.

World War II

Then, World War II struck. resident Franklin Roosevelt created a year-round daylight saving time—called “war time”—from 9 February 1942 until 30 September 1945. Congress enacted the War Time Act on January 20, 1942. Year-round DST was reinstated in the United States as a wartime measure to conserve energy resources.

Consequently, between the war’s end and 1966, confusion regarding time was rampant, especially for certain industries. Some cities and states continued to follow it, others did not. It was almost as inconsistent as before the formation of Standard Time, where different cities and towns all used a different Solar Time. In particular, transportation and broadcasting were burdened with scheduling changes when a state or town began or ended Daylight Saving Time.

Daylight Saving Time re-enacted

When the 1960s arrived, Daylight Saving Time observance in the U.S. was quite convoluted with no agreement about when the clocks should be changed. During this time, some states and cities continued to adhere to the semiannual time change; however, these jurisdictions could start and end daylight saving whenever they wanted. In fact, in a 1963 article, the aptly named Time magazine referred to this confusion as a “chaos of clocks.” Among the contributing reasons to this chaos included that there were 23 different pairs of time-change start and stop times in Iowa alone; the twin cities of St. Paul and Minneapolis, Minnesota observed Daylight Saving Time at different times; and journeying between Steubenville, Ohio to Moundsville, West Virginia—just 39.3 miles—subjected travelers to seven different time changes.

Essentially, it became a battle between indoor and outdoor industries with state and local governments—as usual—failing to bring some common sense into the melee.

Then, in 1966, Congress decided to end the confusion with the Uniform Time Act which President Lyndon Johnson signed into law on 12 April. This law standardized Daylight Saving Time to start on the last Sunday in April and end on the last Sunday in October. States that wished to be exempt from this law could enact legislation, which Hawaii and (most of) Arizona did. However, this act created the necessary uniformity across the U.S. within each time zone, save for those states that filed an exemption.

Changes and Amendments in Modern Times

In 1972, Congress amended the Act in that if a state was situated in multiple time zones, the state could elect to exempt part of the state in one time zone while maintaining that the other part(s) of the state would, in fact, observe Daylight Saving Time.

Then, on 4 January 1974, President Richard Nixon signed the Emergency Daylight Saving Time Energy Conservation Act which required commencement of Daylight Saving Time on 6 January 1974. This Act was in response to an Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) oil embargo in December 1973 that raised the price of crude oil from $2.90 per barrel to nearly $12 per barrel.

In order to “look effective,” Nixon and Congress passed the aforementioned two-year emergency bill under the presumption that the year-round Daylight Saving Time would produce significant energy saving by the reduced use of electric lights and other “unnecessary” power consumption. Of course, other benefits were touted to “sell” the plan. Among these potential benefits included crime reduction, more daylight outdoor playtime, improved traffic safety, and greater economic opportunities.

On 5 October of that year, Congress amended the Act, returning Standard Time on 27 October. The following year, Daylight Saving Time began on 23 February and ended on 26 October. Ultimately, however, what began as a crisis response has now lasted longer than four decades.

In 1986, the Uniform Time Act was, again, amended and set Daylight Saving Time to begin on the first Sunday in April.

But Congress wasn’t finished yet. No siree, Bob. In 2005, its Energy Policy Act extended daylight-saving time in the U.S. which was set to begin in 2007, primarily from the result of the Candy Lobby who fought for the extension of DST so that trick-or-treaters would have more Daylight in the evening of Halloween.

Today, U.S. Daylight Saving Time begins at 2:00 a.m. on the second Sunday of March and ends at 2:00 a.m. on the first Sunday of November. Most western European countries observe Daylight Saving Time beginning at 1:00 a.m. GMT on the last Sunday of March and ending at 1:00 a.m. GMT on the last Sunday of October.

Daylight Saving Time Today

Daylight Saving Time begins with “Spring Forward” at 2am on the second Sunday of March every year. When 2am hits, the clock moves forward to 3am, skipping that hour. This time runs through the summer and into the fall.

Standard Time begins with “Fall Back” at 2am on the first Sunday of November. When 2am hits, the clock moves backward to 1am, repeating the 1am hour over again. It runs through the winter and into spring.

This gives us in the USA about 7-1/2 months of “Daylight Saving Time”, where the sun sets later in the day, and 4-1/2 months of “Standard Time”, where the sun sets earlier in the day.

The Future of Daylight Saving Time

As with anything that impacts everyone’s lives, there is considerable discussion over whether the process of changing the clocks for Daylight Saving Time has outlived its purpose.

What are the Pros and Cons of Daylight Saving Time? Click here to learn more.

Read the interesting stories of great things and bad things about the time changes or Daylight Saving Time in general on our Blog. Click here to view the articles.

What is definitely happening right now is a growing movement to change Daylight Saving Time for the better. Click here to learn more about the Petition and get involved in History and changing the Future!